I was browsing the software engineering part of the Stack Exchange network late one evening, and came across “Why is studying a Lisp interpreter in lisp so important?”

This intrigued me, partly because Lisp is one of those languages that I tend to think of as of historical interest, but not much more. Whenever I mention it to my brother, he gets a misty look in his eyes and says something like “Ooh, I loved that stuff.” I have looked at it once or twice, but didn’t see much reason to go further.

However, that question, and in particular the link to The Nature Of Lisp in Robert Harvey’s answer made me think again. His reluctance to learn it echoed with me, and his amazement that so many very intelligent people praised it made him think there was more to it than met the eye. In particular, he quoted Eric Raymond as saying “Lisp is worth learning for the profound enlightenment experience you will have when you finally get it; that experience will make you a better programmer for the rest of your days, even if you never actually use Lisp itself a lot.” The thought of software enlightenment was enough to keep me awake for a while longer and read further.

OK, so after reading that article carefully, I decided to give it a go. After all, having spent the last few years trying to get my head around functional programming, it seemed like a way to get a good grid on the basics.

The first problem was to decide which dialect of Lisp to learn. There seem to be quite a few, although it seemed to come down to two main branches, Common Lisp and Scheme. I spent some time reading up on tis, and got very confused. I was able to discount Clojure quite quickly, as it is based on Java, so required me to install that. Now I have nothing against Java, but the thought of installing yet another heavy framework on my machine put me off, so I decided to pursue my aim a different way, ie by seeing which I could get running on my machine with the least effort.

The problem is of course that most Lisp programmers don’t use Windows, so most Lisp distributions are geared towards people who have all sorts of utilities installed, and work from the command line. Now I’ve nothing against that in principle, I did it for enough years when I worked in Unix systems, but I’m getting old and lazy and wanted a Windows experience. I guess I’ve been spoiled by Visual Studio, which (despite a few quirks) is an amazing IDE. I also try to avoid installing more software than necessary on my machine, and most of the distributions I saw required all manner of auxiliary software to get going.

After some searching, I came across Portacle. This is an Emacs-based Lisp system that is totally portable. You can just unzip the distribution, double-click the executable and get coding. It doesn’t require anything else, and doesn’t even require installing. See you next year, I’m off into Lisp-land!

To make things even better, I found that the author of the Apress book Practical Common Lisp had put the entre book online. This meant I could get going immediately.

The one thing that marred this was Emacs. Now don’t get me wrong, Emacs is very powerful. I used to be a bit of a wizard at it some decades ago, but as I said, I’ve grown old and lazy since then. Learning a whole new set of keyboard commands for every operation proved to be slow, and made the experience less exciting than it might have been.

I then came across Corman Lisp. This another open source, Windows-based Lisp IDE, but has the massive advantage of looking and working like a regular Windows application. Even better, it has the ability to create Windows executables, so should I ever produce anything remotely useful in Lisp, I could turn it into a standalone application. As this also used Common Lisp, I could just carry on from where I was with Portacle.

Well, never one to keep my head on what I was supposed to be doing (or in this case, what I wasn’t really supposed to be doing, but what I was doing), I kept looking around at other Lisp distributions and dialects. Along the way (several times actually), I came across Racket, which (if I got it right) is built on Scheme, which is itself a different dialect of Lisp from Common Lisp. At first I dismissed it, as my impression was that Common Lisp was more, well, common, but having read around at what other people thought, and having looked a bit more at it, I decided to give it a go.

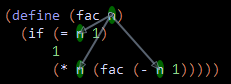

I was very pleasantly surprised on two counts. Firstly, DrRacket, the IDE for Racket is even superior to Corman Lisp. For example, if you hover your mouse over a symbol, you get a visual indication of where it is used and/or defined (depending on what you hover over). For example, if you hover over a function parameter, it shows you where the parameter is used…

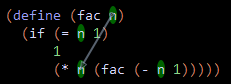

Although you can’t tell form the screenshot, my mouse was over the n on the first line, and the arrows showed me where n was used in the body of the function. If I hover over an instance of n in the body of the function (in this case, over the first usage on the last line), it adds an arrow showing where the symbol was defined, as well as highlighting other usages…

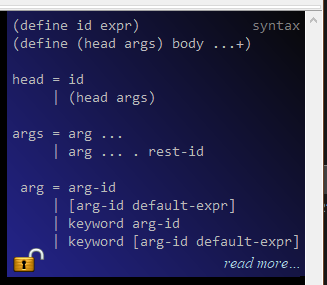

Also, in the top-right corner of every DrRacket tab is an arrow you can hover over, and it pops open a flyout with syntax for whatever symbol the mouse cursor is on…

I’m still getting my head around what this all means, but I can see that it’s going to be a big help, especially the “read more…” link at the bottom.

The other thing I like about Racket is that the syntax seems easier than Common Lisp. This is probably subjective, and I’m sure those familiar with Common Lisp may argue, but as a beginner, I find myself more able to write Racket code than I was with Common Lisp. I don’t think it matters too much in the long run, as this is really only for my own edification, so as long as I can learn the language, the exact dialect is probably not important. However, as Racket is closely related to Scheme, which seems to be a very well used Lisp, if I ever did want to do this stuff commercially, I could hopefully switch to Scheme if Racket proved to be too limiting or obscure.

As this post is getting a bit long, and I’m rambling as usual, I’ll end here. Hopefully I’ll report more when I’ve explored Racket in more depth.

Be First to Comment